Hacking the TL-WPA4220, Part 2: The Command Injections

In the first blog post of this series, we took a look at a previously disclosed vulnerability in the TL-WA850RE, analyzed the httpd binary, and understood how this vulnerability could be exploited. In this post, we are going to see how we can use this knowledge to find similar (unreported) vulnerabilities for the HTTP server of the TL-WPA4220 Powerline WiFi extender (CVE-2020-24297).

In the previous post, we started from the vulnerable endpoint and the parameters needed to exploit the vulnerability (all of which we knew from the exploit code), so we followed the path in the disassembled binary until we reached the vulnerable code. That allowed us to understand exactly what was the flaw that led to the possibility of executing arbitrary code on the device.

In this post, we are going to do the reverse for the TL-WPA4220: first, we will start by locating spots where the same flaw is potentially present. Then, for those spots that are actually exploitable, we will follow the code backward until we find the affected endpoint. Also, during this process, we will be able to determine what are the parameters that we need to pass in the requests (as well as their values) to reach the vulnerable part of the code.

Previously, in Hacking the TL-WPA4220

Before proceeding, let us remind some important facts that we learned analyzing the TL-WA850RE:

-

The calls to the function

execFormatCmd, which is basically a wrapper ofvsprintfandexecve, is where the vulnerability occurs. This function can be used like that:var = "Hello World!"; execFormatCmd("echo %s", var);This code would execute the command

echo Hello World!. The vulnerability happens when one of the parameters passed to this function is supplied by the user without any validation or sanitization. For example, let’s imagine the user can set the value ofvarabove. Setting it tovar = "Hello World!; ping 127.0.0.1", the call to theexecFormatCmdwould execute two different commands:echo Hello World!andping 127.0.0.1, as the semi-colon acts as a separator between them. This is what can allow arbitrary code execution. -

The function

httpGetEnvis used to obtain parameter values from HTTP requests. For instance:value = httpGetEnv(param_1, "id");would obtain the value of the parameter

idand store it in the variablevalue(for what matters, we don’t need to worry about the variableparam_1). -

The function

httpRpmConfAddAndRegisterFileis used to register callbacks for endpoints of the HTTP server. For example, if we see:httpRpmConfAddAndRegisterFile("/some/endpoint", some_function);it means that when the server receives a request to the endpoint

/some/endpoint, the functionsome_functionwill be executed.

With that in mind, we are ready to start with our new challenge!

Getting the Firmware

The first thing we need to do to analyze the TL-WPA4220 is, obviously, getting the firmware. In this post, we will only analyze version TL-WPA4220(EU)_V4_190326 since (before the patch) it was the latest release for the hardware version 4, which was the one of my newly bought TL-WPA4220. However, looking at older versions can sometimes give nice surprises: some secret key that was embedded by mistake and removed in later versions, bugs that were not completely fixed in newer versions, etc.

In this case, actually, we would find one of such surprises: the binaries in a previous version (TL-WPA4220(EU)_V4_180108) contain debug symbols, which can be really helpful when we are reverse-engineering and looking for bugs. Since this debug information is not strictly necessary to find the vulnerabilities in this post, we will not use it here. But just so you know, we can import the function names of the old version to the newer version using the BinDiff Helper Plugin for Ghidra. It’s pretty cool, I recommend taking a look at it!

Anyways, after downloading the TL-WPA4220(EU)_V4_190326, we will unzip it and use binwalk to extract the firmware, just as we did in the previous post. Again, after the extraction, the httpd binary can be found in the directory squashfs-root/usr/bin. Again, the architecture of the binary is MIPS.

Finding Vulnerable Candidates

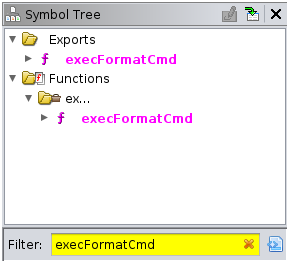

Now that we have our binary, we will try to locate vulnerabilities building on the knowledge that we gained by analyzing the previously known exploit for the TL-WA850RE. As we mentioned above, it boiled down to the use of the function execFormatCmd with a non-sanitized POST parameter that could be manipulated by the user. After opening the httpd binary with Ghidra, we can look for this function, and we will see that this binary also has it (recall that, since the function is an export, we can search it by name even if we have no debug symbols):

Our goal here is to find uses of execFormatCmd where the second parameter is provided by the httpGetEnv function since, as we saw, this means that it is set by an HTTP parameter, and therefore we can manipulate it to achieve a command injection.

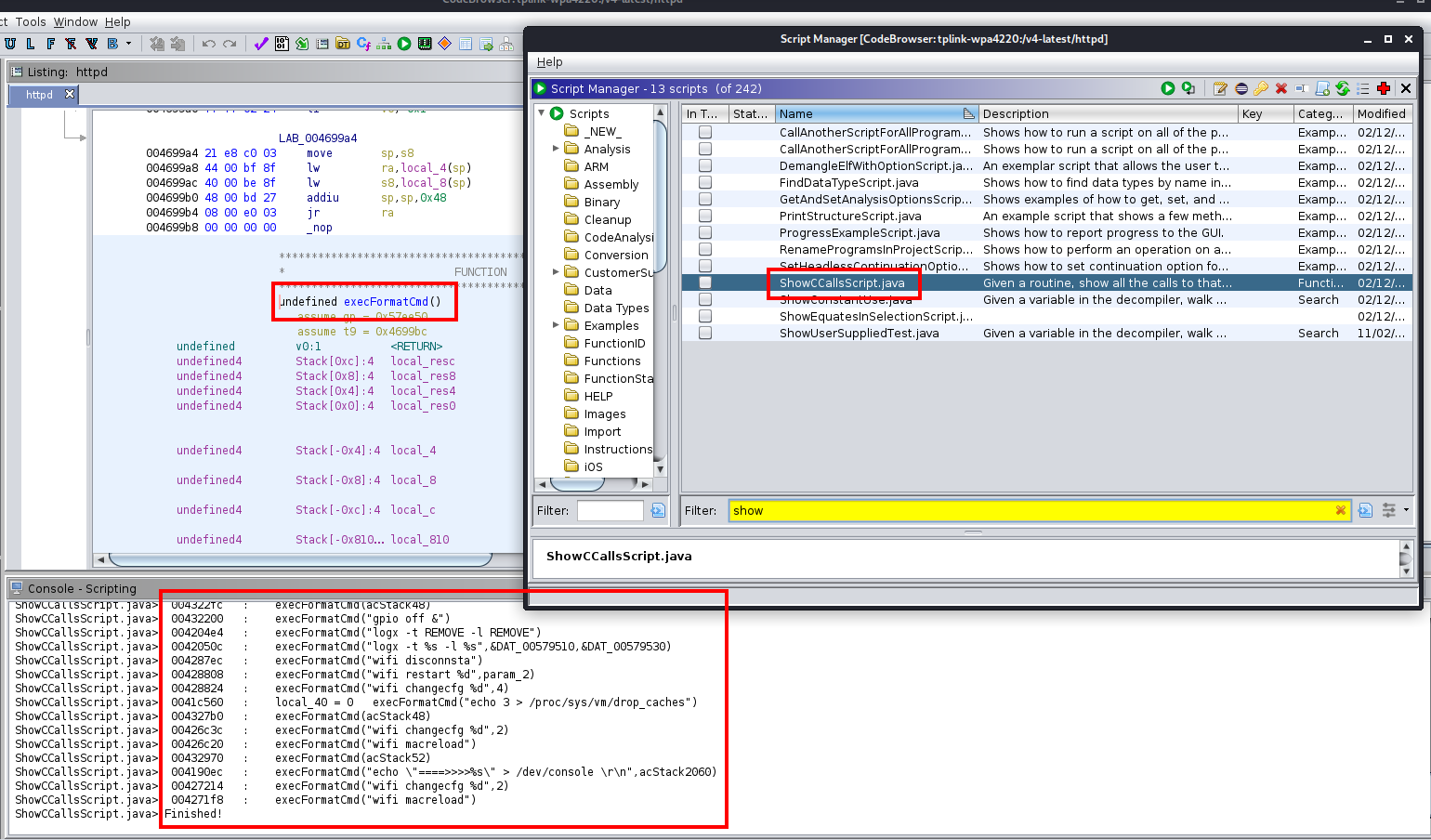

Instead of looking for cross-references of the execFormatCmd function, we will use the built-in scripts in Ghidra, specifically the script ShowCCallsScript.java. This script is pretty convenient because we can see quite straightforwardly possible candidates of vulnerable calls to the execFormatCmd function without having to go back and forth around the code. To execute this script, we go to the disassembly of the execFormatCmd function, we click on Window -> Script Manager, search for the script, and double-click it. After doing that, in the console window we will see the calls of this function with the parameters passed to it:

The candidates to be vulnerable are calls to the function that have a parameter of type string that can be controlled by the user. Hence, we can readily discard many of the calls. Two examples of calls in the image above that are not candidates to be vulnerable are:

execFormatCmd("wifi restart %d",param_2). This call is not vulnerable because the parameter (even if it were user-supplied) is cast to an integer, so there is no way we can achieve a command injection with that.execFormatCmd("wifi macreload"). Here there is no parameter, so we can discard it right away.

On the contrary, two examples of candidates to be vulnerable calls are the following:

execFormatCmd(acStack52). We need to take a look at this sinceacStack52must be of type string. However, we need to determine how the value of this variable is set: is it somehow user-provided, or is it copied from a hard-coded value?execFormatCmd("echo \"====>>>>%s\" > /dev/console \r\n",acStack2060). Same as above. Note that here the value ofacStack2060is explicitly cast to a string.

Out of the 69 calls to the execFormatCmd, only around 20 are candidates to be vulnerable. Inspecting these one by one, we only find the following 3 that have a parameter that is user-supplied:

execFormatCmd("plc removeDev -m %s",iVar1), at address0x00420a30execFormatCmd("plc addNew -p %s",pcVar2), at address0x00420ba8execFormatCmd("plc setNtwName -n %s",uVar1), at address0x00420e14

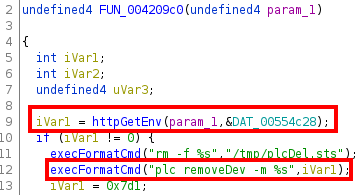

Let’s look at the first one. Going to address 0x00420a30, we see it is inside a function named FUN_004209c0. The decompilation of this function starts with:

As we can see, the value of iVar1 is the return value of the httpGetEnv function, which we know gets the value of the desired parameter in the HTTP request. Looking at the string stored in DAT_00554c28 we actually see that this parameter is key. This means that if we can set this parameter to, let’s say, 123; echo You have been pwned, we know that echo You have been pwned will be executed on the device.

The Path to the Vulnerability

We have apparently found a vulnerability, so now it’s time to see how we can trigger it. This is just a matter of tracing back the function calls and checking the conditions that will lead us to the vulnerable code.

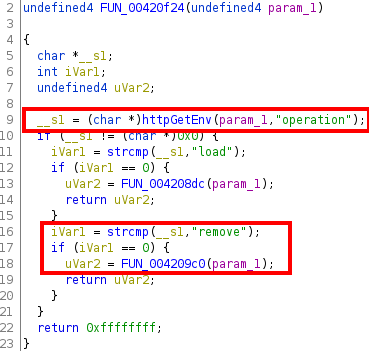

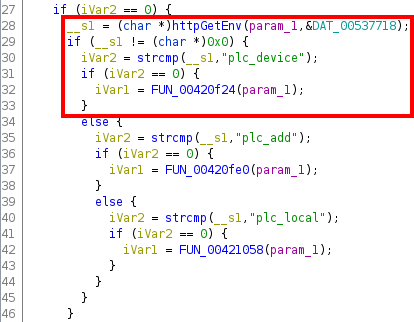

Let’s focus again on the call at 0x00420a30, which we saw is inside the function FUN_004209c0. There is only one cross-reference to this function, which is inside FUN_00420f24:

Reading the code, we can see that the condition for FUN_004209c0 to be called is that the value of the parameter operation (stored in the variable named __s1) is equal to remove.

Now we look for cross-references of the function FUN_00420f24, and again we only find one in the function named FUN_00421130. Looking at this function we see the following (we show only an excerpt):

Inspecting the contents of the global variable DAT_00537718, we see that it contains the string form. Then, from the above image we can see that, in order to call FUN_00420f24, the value of the parameter form (stored in the variable named, again, __s1) has to be equal to plc_device.

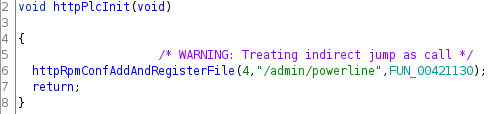

Finally, looking at the cross-references of the function FUN_00421130 we see that it is only used in the function httpPlcInit, passed as a parameter to the function httpRpmConfAddAndRegisterFile:

Recall that the function httpRpmConfAddAndRegisterFile registers callbacks of the different available endpoints of the HTTP server, in this case, the endpoint /admin/powerline.

So, with the information we have, we know how to reach the vulnerability: we have to make a request to the endpoint /admin/powerline, passing the parameters form=plc_device and operation=remove. Then, we can use the parameter key to inject a command, as we have seen above. That’s it!

The Other Endpoints

We can do the same analysis with the two other vulnerable candidates to see how they can be reached. However, when doing that we will see that actually just one of the remaining two candidates is actually vulnerable.

Indeed, the call at address 0x00420ba8 is pretty similar to the one we have investigated above. The same procedure will lead to seeing that the affected endpoint is also /admin/powerline. In this case, however, we need to pass the parameter operation equal to write (instead of remove), and the parameter form equal to plc_add (instead of plc_device). Moreover, the vulnerable parameter (where we can perform the command injection itself) is devicePwd instead of key.

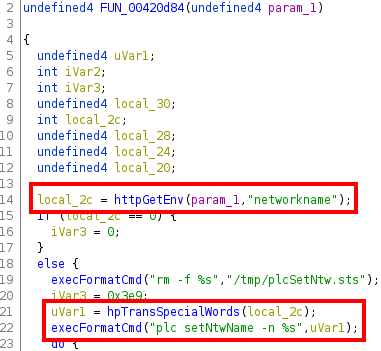

Regarding the call at address 0x00420e14, things go a little bit differently, and we will realize that it is actually not vulnerable. Let’s look at the decompilation of the function that contains this address (which is FUN_00420d84):

We can see that the value returned by the function httpGetEnv (the variable local_2c, that contains the value of the parameter networkname) is passed to the function hpTransSpecialWords before passing it to execFormatCmd. If we search for this function, we will see that it is actually an import. We can determine the library where it is imported from simply by grepping for it in the /lib folder of the firmware:

$ grep -r hpTransSpecialWords squashfs-root/lib/*

Binary file libplcapi.so matches

If we use Ghidra to analyze this function we will see that, essentially, it escapes all non-alphanumeric characters of the input string. Thus, the use of this function with our input parameter kills any possibility to inject a command, since the characters needed (for instance the semi-colon, or a back-tick, etc.) will be escaped. In other words, there was already a patch for the vulnerability, but it was only applied to one of the three vulnerable spots!

Conclusions

In this post, we have seen how we could find two unreported command injection vulnerabilities of the TL-WPA4220, building on the knowledge we acquired by analyzing a previously disclosed vulnerability of a similar device. This highlights the fact that vendors might repeat the same mistakes over and over, so we can take advantage of it to find new bugs.

Also, we detected that a fix for this kind of vulnerability was already present in the binary. However, this fix was only used in one of the three potentially vulnerable spots.

Moreover, during this process, we used some pretty cool features of Ghidra that helped us to find these vulnerabilities. In particular, we used the script showCCallsScript to find all the calls of the function execFormatCmd, and quickly determine the ones that could be potentially vulnerable.

Finally, with the knowledge that we have obtained, we are almost ready to exploit these vulnerabilities: we know the vulnerable endpoints, the vulnerable parameter, and the parameters that are needed to reach the vulnerable code. It only remains to know how to communicate with the HTTP server - something that, unexpectedly, is not quite straightforward. In the next post, we will explain exactly why and we will show the exploit in action.